0. Introduction to Graph Theory

I will be creating a series of blog posts as well as presentations on graph theory. The blog post is inspired by Prof. Yufei Zhao's book Graph Theory and Additive Combinatorics. The goal for my blog posts is to provide a more friendly introduction to concepts in graph theory. If you are a high school student interested in math outside of your currilum, if you are a math olympiad enthusiast, or if you are a college student taking an introductory graph theory class, I hope you all can find my blogs useful. I will be discussing selected topics and problems of graph theory as well as providing solutions to some exercises.

So, what is graph theory?

ChatGPT: "Graph theory is a branch of mathematics that studies the properties and structures of graphs, which are mathematical representations of networks of objects or relationships between them. Graphs can be used to model a wide range of problems in various fields, including computer science, engineering, social sciences, biology, physics, and more. Some of the basic concepts in graph theory include vertices (or nodes), edges, and various types of graph such as directed, undirected, weighted and unweighted."

First, we introduce some notations to define a graph.

Notations¶

We write a graph as \(G=(V,E)\), where \(V\) is the set of vertices and \(E\subseteq \{(x,y)|x,y\in V\}\) is the set of edges.

When there's a direction for the edges (e.g. \(x\to y\)), we say the graph is directed, otherwise it's undirected. We will focus on undirected graphs in our future posts.

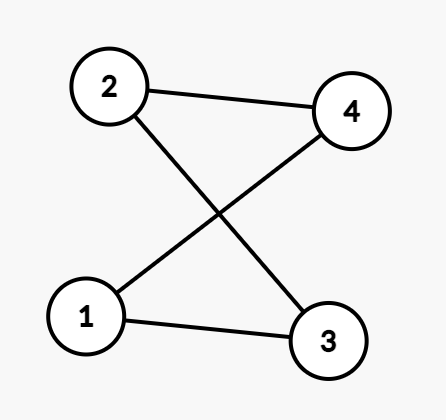

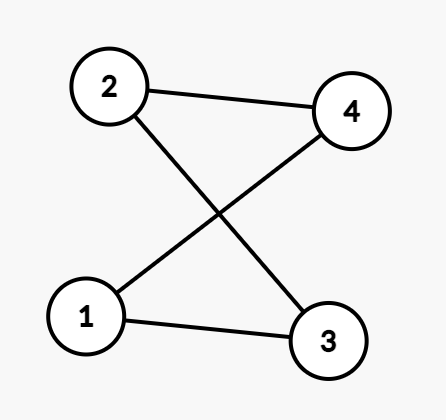

For example, when \(V=\{1,2,3,4\},E=\{(1,3),(1,4),(2,3),(2,4)\}\). The graph looks like this:

This is also known as a \(K_{2,2}\) graph, which means we have two vertices on the left and other two on the right, and every vertex on the left is connected with every vertex on the right.

Generally, we define the complete bipartite graph \(K_{s,t}\) to be a graph with \(s\) vertices in one part and \(t\) on the other, and any edges in between the two parts are connected. Below is an example of \(K_{5,3}\):

Moreover, \(K_r\) is the complete graph on \(r\) vertices, which means \(E=\{(x,y)|1\le x < y\le r \}\) . It is also known as a \(r\)-clique. Below is the graph \(K_7\).

In a graph \(G=(V,E)\), we say two vertices \(u\) and \(v\) are neighbors or adjacent if there exist an edge \((u,v)\in E\) . In the above example, \(1\) is a neighbor of \(4\) but not a neighbor of \(2\).

A neighborhood of \(u\) is defined as the set of all \(u\)'s neighbors. Formally, \(N(u)=\{v|(u,v)\in E\}\). In the above example, \(1\)'s neighborhood contains \(3\) and \(4\), so \(N(1)=\{3,4\}\).

The degree of \(v\) is the number of edges that contains \(v\), denoted as \(\deg v\) . In undirected graphs without self-loops (weird edges like \((u,u)\)), it's clear that \(\deg v = |N(v)|\).

Handshaking Lemma¶

Claim: For a graph with \(m\) edges, we have

Proof: For each edge \((u,v)\), we count it twice on the left hand side (in \(\deg u\) and \(\deg v\)), thus it sums up to \(2m\).

Handshaking Lemma: In a undirected graph, the number of vertices with odd degree is even.

The name of this theorem comes from a famous mathematical problem, which is proving that: in a party, the number of people who shake hands an odd number of times must be even.

Proof: Assume that that number is odd, then for the left hand side you get \(1\times 1 + 0\equiv 1\pmod 2\) (odd times odd + even = odd). However, the right hand side is even. Contradiction! Thus the statement holds.

Walks, Paths, and Cycles¶

In an actual graph, we might want to travel from a point to another point along some roads conneting them. We also have similar concepts in graph theory, called a walk, which is defined as a sequence of edges \((e_1,e_2,\dots,e_{n-1})\) and vertices \((v_1,v_2,\dots,v_n)\) in a graph such that \(e_i = (v_i,v_{i+1})\) is the edge connecting \(v_i\) and \(v_{i+1}\) in the graph.

For example, in our previous graph, if we walk along \((1,3),(3,2),(2,4)\), then we passes through the vertices \(1,3,2,4\), and these two sets together forms a walk.

Moreover, a graph is called connected if there is a walk from any vertex \(x\) to any other vertex \(y\).

We can define more terms based on our walk! What if we never travel through the same edge twice? A trail is a walk in which all edges are distinct \((e_i\ne e_j)\).

What if we never travel through the same vertex? A path is a walk in which all vertices are distinct \((v_i\ne v_j)\).

What if we are on a trail that travels back to our starting point? A trail where the first and the last vertex are the same is called a cycle. \(1\to3\to2\to4\to 1\) is a cycle, since it starts and ends at \(1\).

Claim: If a graph has no cycles, it must have a vertex with degree \(\le 1\).

Proof: Let's prove by contradiction! Suppose none of the vertex has degree \(\le 1\), then we can pick any vertex \(v_0\) and start our trail there, picking the next edge to be any untraveled edge from this point and continuing this process. Since there's no cycle, the trail will eventually end at some point \(v_n\ne v_0\). However, this would mean that we traveled to \(v_n\) at least twice because \(\deg v_n > 1\)! We can just start at \(v_n\) and follow the same trail to form our cycle. Contradiction!

We call a graph without cycles an acyclic graph.

Trees¶

You might not learn anything about graph theory before, but you definitely have seen trees in graph theory. It looks like a mindmap:

There are several definitions about a tree in graph theory and they are indeed equivalent!

- A tree is a graph in which any two vertices are connected by exactly one path.

- A tree is a connected graph without any cycles.

- A tree is a connected graph without any cycles, but a cycle will form if any edge is added to it.

- A tree is connected, but would become disconnected if any edge is removed from it.

We will not go into proving the equivalence of all these statements here but it will be left as an exercise.

Next, draw your own trees and count the number of vertices and edges. What do you find?

Claim: An \(n\)-vertices tree has \(n-1\) edges.

Proof: We can prove by induction on \(n\). When \(n=1\) the tree has no edges so our claim holds.

When \(n > 1\), let \(T\) be a tree with \(n\) vertices. Since \(T\) has no cycles, there exists a vertex \(v\) in \(T\) such that \(\deg v\le 1\) by the previous claim we made about acyclic graph. \(T\) is connected so \(\deg v =1\).

Thus, we can consider the graph \(T'=T-v\) that we get by deleting the vertex \(v\) in \(T\). \(T'\) is still connected and has \(n-1\) vertices. By induction there are \(n-2\) edges in \(T'\) so \(T\) has \(n-1\) edges.

Problems¶

- If there exists a walk from \(x\) to \(y\), can you always find a path from \(x\) to \(y\)? What about trail?

- Let \(\delta\) be the minimum degree of \(G\), and suppose that \(\delta \ge 2\). Prove that \(G\) contains a path with \(\ge \delta + 1\) edges.

- If \(G\) is a tree and the sum of the degree of all vertices is \(S\), how many vertices does \(G\) have?

- An Eulerian trail is a trail in a graph \(G\) that visits every edge exactly once. It was first discussed by Leonhard Euler while solving the famous Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem. Euler proved that such trail exists only when the degree of all vertices are even. Can you prove it?

- Prove that a connected graph has an Eulerian trail if every vertex has an even degree.

- Prove that the statements about trees are all equivalent.

- We call a graph bipartite if it is a subgraph of a complete bipartite graph. In other words, the vertices in a bipartite graph can be separated into two groups such that all of the group's edges only cross between the groups. Prove that a graph is bipartite if and only if it has no cycles of odd length.

- Let \(G\) be a graph. Prove that it is possible to partition the vertices into two groups such that for each vertex, at least half of its neighbors ended up in another group.